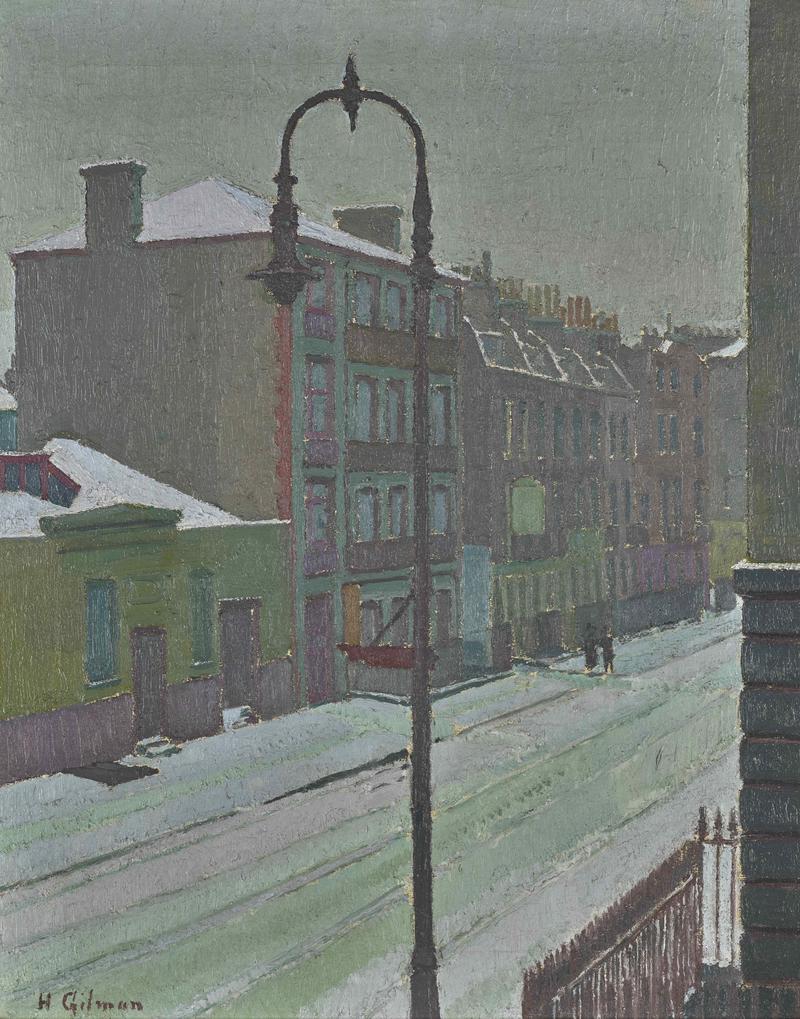

A London Street Scene in Snow

Recently Exhibited

Pallant House Gallery, Harold Gilman: Beyond Camden Town, 2 March 2019 to 9 June 2019, cat. no. 71, illustratedAdditional Exhibition History

London, Arts Council, Harold Gilman 1876–1919, 1st January – 31st December 1954, cat. no.40, illustrated pl.IV, with Arts Council tour to Manchester Art Gallery, Manchester and Tate, LondonLondon, The Reid Gallery, Harold Gilman 1876–1919, 3rd - 25th April 1964, cat. no.34, illustrated

Stoke on Trent, City Museum and Art Gallery, Harold Gilman 1876-1919, 10th October - 14th November 1981, cat. no.89, illustrated p.27, with Arts Council tour to City Art Gallery, York; Museum and Art Gallery, Birmingham and Royal Academy of Arts, London, Thomas Agnew & Sons, November - December 1988 (details untraced)

Nottingham, Djanogly Gallery, Harold Gilman: Beyond Camden Town, 17 November 2018 to 10 February 2019, cat. no. 71, illustrated

Gilman understood that the truly modern subject was the city, its back rooms and bed-sits and the quiet dignity of the isolated people who inhabited them. The perceived dislocation of his art may be seen in the painterly A London Street Scene in Snow which is almost completely disassociated from the urban sprawl and bustle. Always happiest with the static image, his cityscapes avoid the continual movement of the urban world. By fragmenting the image into blocks of dreamlike antagonistic colour, and through the removal of almost all staffage, Gilman imposes an isolating and tense dialectic entirely in keeping with the atmosphere of the period. The humming intensity of blocks of dissonant colour highlight our quiet isolation from the landscape. There is no let-up in the colour of the flat sky so our eyes cannot escape upwards and beyond the landscape. The result is muted and muffled, intimate and aloof. Although the painting has a defined and rigid geometry, we are left off-kilter by the image through the unusual viewpoint and discordant colours.

Gilman exhibited at the Salon des Indépendants (a non-jurist association) in Paris which meant that he was aware of the art movements occurring in France at the time, principally the Fauves and the Post-Impressionist styles of Van Gogh, Gauguin and Cézanne. He helped to form the Salon’s London equivalent, the Allied Artists’ Association (AAA). An inspirational visit to Paris in 1911 and Roger Fry’s Manet and the Post-Impressionists exhibition in 1910-1911 proved to be pivotal for Gilman and his palette underwent a radical change, employing an exciting breadth and exuberance. His devotion to the, ‘vehement brushwork, … loaded texture and the garish colours of Van Gogh’ (Wendy Baron et al, Harold Gilman, Beyond Camden Town, 2018, p. 12) was to remain for the rest of his life.

Despite taking on board these avant-garde influences, Gilman retained a strikingly English conservatism and sense of quiet gravity that was never dictated by the current vogue. He was a founder member of the influential Camden Town Group who held their first exhibition in June 1911 and which, although short-lived, was pivotal in the developments of modern British art. The groups’ work was vernacular - taking subjects from everyday London life and human experience whether beautiful or banal. The outmoded ideals of Academic art were replaced with direct observation of life and how it was really lived and through the use of colour, paint techniques and naturalism of subject matter, a direct emotional understanding is elicited from the viewer. To many, their output was considered an outrage against good taste. Gilman’s subject matter and portrayal of the drab, every-day, and his use of colour as the main driver of narrative were innovative and shocking. This was painting for the modern world, made as the old order was being torn apart by the unprecedented horror of the First World War.

On summer visits to Sweden (1912) and Norway (1913), Gilman experimented with vivid colour, often applied in a patchwork of flat, simplified areas of paint which continued to inform his palette (and subject matter) particularly in the use of soft shades of lilacs, saffron yellows, lime greens, Carl Larsson reds and Gustavian blues. He took on the, ‘Scandinavian taste for clean, uncluttered lines and simple proportions’ and his paintings, seemingly straightforward in composition, mask their intricacy.

Until his death in 1919 from Spanish flu, Gilman searched for a personal and distinctive form of art which he directly presented with a deep stillness and dignity. It is possible to read a particular sense of loneliness and dislocation into Gilman’s resonant poetic meditations on the urban experience which are evocative of a turbulent and convulsive time in history.