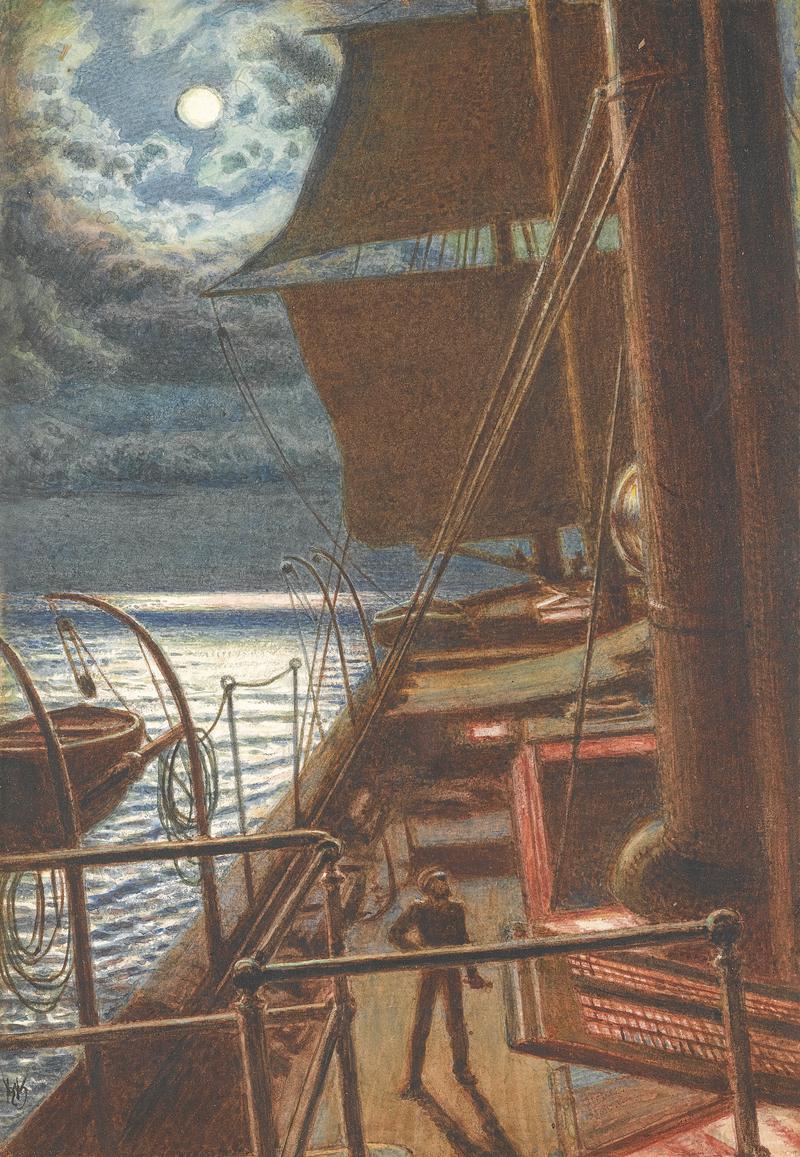

Homeward Bound (The Pathless Waters)

Recently Exhibited

Watts Gallery - Artists’ Village, Compton, Moonscapes, 1 April - 23 June 2019Additional Exhibition History

London, Old Watercolour Society, 1871, no. 256Watts Gallery - Artists’ Village, Compton, Untold Stories: Pictures from Private Collections, November 2016 to February 2017

‘The moon makes for herself a clear path through clouds which crown, or rather encircle, her head with a halo of iridescent light. The sea beneath shines as burnished silver.’ The Art Journal

Homeward Bound was painted in 1869 and sent to England in the autumn of the following year to be exhibited at the Old Watercolour Society, as the artist’s letter of 12 October to A.W. Hunt reveals: ‘I have lately sent home a couple of water colour drawings and I wish to give them to be mounted and framed to a safe man…. [They] are one – a view in the interior of the Mosque Ar Sakreh here – the other a Moonlight at Sea.’ Judith Bronkhurst has suggested that the picture was painted during Hunt’s August 1869 voyage from Brindisi to Jaffa in Israel. This is confirmed by Stephen’s review in the Athenaeum of 13 May 1871, ‘The Pathless Waters … a rapidly-made sketch of the sea and moonlight as apparent from the deck of a steamer, is … remarkable for luminosity and richness of colour; … The moon and clouds about her face are very fine’. The Art-Journal commented: ‘Holman Hunt again attempts to paint impossibilities. In The Pathless Waters (256), he strives to seize on a lovely phenomenon of sky and sea, familiar to all who have voyaged on the Mediterranean. The moon makes for herself a clear path through clouds which crown, or rather encircle, her head with a halo of iridescent light. The sea beneath shines as burnished silver.’

Homeward Bound and Interior of the Mosque Ar Sakreh (later in the collection of Lord Leverhulme) were bought by the portrait painter Rudolf Lehmann (1819-1905), to whom Hunt wrote on 10 March 1873: ‘Thank you for your kind note which encloses the cheque for £204/15 … You are more than prompt in paying me before the works are sent home: this however shall be very soon. I am delighted that you have got them. I feel satisfied to a high degree that I withdrew them from sale until now for so good a fate as this in store for them’. Hunt was friends with Rudolf Lehmann and his brother Frederick, a noted amateur violinist and partner in an engineering firm who was also a patron of Albert Moore and friend of Millais, Leighton and the writer William Wilkie Collins. Later in the nineteenth century Homeward Bound passed into the collection of the accountant Edward Frederick Quilter, son of the eminent stockbroker and art collector Sir William Cuthbert Quilter M.P. and brother of the composer Roger Quilter. Among the Victorian masterpieces in Cuthbert Quilter’s collection were Rossetti’s La Bella Mano, Burne-Jones’s Green Summer, Marianne by Waterhouse,Cymon and Iphigenia by Leighton, The Last Muster by Herkomer, Joan of Arc by Millais and one of Holman Hunt’s most famous paintings, The Scapegoat.

Judith Bronkhurst has drawn comparison between Homeward Bound and Moonlight at Salerno of 1868 in the depiction of moonlight on the ocean, the former depicting: ‘the full moon (indicated by bare paper) [that] illuminates the surrounding indigo sky and pale turquoise/green clouds and casts a bright pinkish gleam on the sea in the middle distance. The horizontal banding in the left of the drawing is achieved with great economy of means – the moonlight areas are hints of ochre highlighting on bare paper.’ Comparison might also be made with Hunt’s watercolour, Fishing-Boats by Moonlight, c. 1869 (The Higgins Art Gallery and Museum, Bedford).

One of the founders of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Holman Hunt sought to revitalise art by emphasising the detailed observation of the natural world in a spirit of quasi-religious devotion to truth. Hunt’s works were not initially successful and were widely attacked as his pursuit of truth to nature was seen by critics as clumsy and ugly. He did acquire some early note for his intensely naturalistic scenes of modern rural and urban life, such as The Hireling Shepherd (1851, Manchester Art Gallery), Our English Coasts (1852, Tate Britain) and The Awakening Conscience (1853, Tate Britain). However, it was for his religious paintings that he became famous such as The Light of the World (1851–1853, Keble College, Oxford); a later version (1900) toured the world and now has its home in St Paul’s Cathedral.

Hunt made his first visit to Jerusalem in 1854-55 hoping to rediscover the biblical lands in Egypt and Palestine after a crisis of religious faith and to employ his ‘powers to make more tangible Jesus Christ’s history and teaching’. He wanted to confront the relationship between faith and truth. His only painting from his first trip to Jerusalem was The Scapegoat (1854-56, Lady Lever Art Gallery and Manchester Art Gallery). Hunt wrote to William Michael Rossetti on 12 August 1855, ‘I have a notion that painters should go out, two by two, like merchants of nature, and bring home precious merchandize in faithful pictures of scenes interesting from historical consideration or from the strangeness of the subject itself.’

William Holman Hunt married Fanny Waugh in 1865. Hunt was again to travel to the Holy Land, with Fanny at his side. Fanny was seven months pregnant when they arrived in Florence where they were confronted by the ban on Italian ports and they decided to stay there. Here Fanny gave birth to their son, Cyril Benoni in October 1866 but sadly died a few months later in December 1866. She was buried in the English Cemetery in Florence, beside the tomb of Elizabeth Barrett Browning. Hunt returned to England with his baby boy. He again made a visit to the East in 1869, stopping on his way in Florence in June 1868, to design and supervise the building of the memorial to his late wife. The tomb was erected in the Protestant Cemetery near the Porta Pinti in Florence. He then continued on to Jerusalem by sea from the Port of Brindisi to Jaffa.

When Hunt painted Homeward Bound, the death of his wife must have been at the forefront of his mind. Hunt was always aware of the symbolism of his surroundings. It is possible that he saw the moon in terms of Christian symbolism, as having the power to shine through the darkness giving the comfort and support of faith and a connection to something greater than the immediacy of suffering. The moon is representative of God’s love as it leads the ship Homeward. Hunt was, in fact, not heading home but onwards to Jerusalem which perhaps he viewed as his spiritual home. Similarly, the painting accompanied by the title, may suggest an allegory for God guiding a ship (and Fanny’s soul) towards his love and protection. With this, Hunt appears to be painting in the tradition of the sublime. The artists of the Romantic movement such as Turner (1775-1851), Constable (1776-1837) and Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840) used light to understand and depict a new appreciation of spirituality. The Romantic disillusionment with the materialism of society saw a parallel with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and Hunt especially sought to depict nature as a divine creation. B.G. Windus, who was an early patron of the Pre-Raphaelites, had a famous collection of paintings by Turner which during Turner’s lifetime was the most distinguished of its kind and people could view these works, by appointment. Ruskin spent a great deal of time studying Turner’s work there and it is interesting that B. G. Windus also owned Hunt’s The Scapegoat and The Sphinx, Giza looking toward the Pyramids of Saqqara (1854, Harris Museum and Art Gallery, Preston).

The moon appears in several of Hunt’s works. In the richly emblematic The Light of the World (1851-53, Keble College, Oxford), the halo around Christ’s head is symptomatic of the moon in a night-time setting. It is an allegorical painting representing the figure of Jesus preparing to knock on an overgrown and long-unopened door, illustrating Revelation 3:20: ‘Behold, I stand at the door and knock; if any man hear My voice, and open the door, I will come in to him, and will sup with him, and he with Me.’ Hunt, feeling he had to explain his symbolism fifty years after he had painted the picture, stated: ‘I painted the picture with what I thought, unworthy though I was, to be by Divine command and not simply as a good Subject.’ The luminous Christ and the Two Marys, (Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide) was begun in 1847 and returned to in 1897 when Hunt had developed into a painter for whom religion became a recurring theme. It seems to glow with an inner light and the halo surrounding Christ is like a circular rainbow indicating spiritual illumination, coloured with brilliant colours and shimmering light. The light surrounding the moon in Homeward Bound has the same circular format, although in this case the moon replaces Christ’s face. The moon appears in both Hunt’s paintings of The Scapegoat.

Hunt’s later painting, The Ship (1875, Tate Britain), was begun on a voyage to the East with his second wife, Edith, the sister of Fanny, whom he married in 1875. Their marriage was not permitted in Britain and so they had to live abroad and Hunt built a house in Jerusalem for this purpose. He painted The Ship largely from memory, rather than from life. The ship could be seen as a metaphor for Hunt’s life and religious uncertainty. He wanted to suggest the idea of life as a journey, ‘with no guidance from Him but the name of the port to be reached … nothing but the silent stars to steer by for the heavily freighted ship and no welcome till the land is reached.’ The man at the wheel in The Ship has a similar stance to the man in Homeward Bound and he wears a similar cap. It has been suggested that the figure is Hunt himself, and the woman seated looking up at the night sky is Edith.