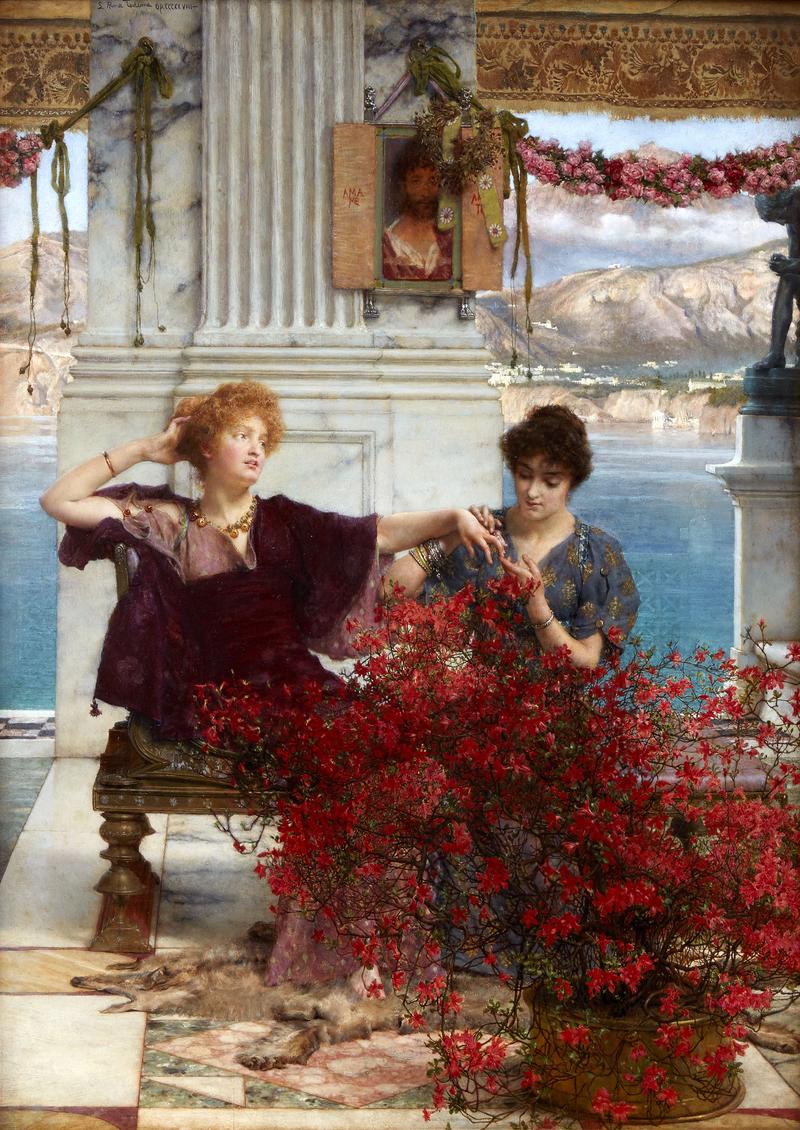

Loves Jewelled Fetter (The Betrothal Ring)

Exhibition

London, New Gallery, 1895, no. 73London, Art Gallery of the Corporation of London, Guildhall, Loan Collection of Pictures by Painters of the British school who have flourished during Her Majesty’s Reign, April 7-July 14, 1897, no. 117 (lent by George McCulloch, Esq.)

Glasgow, International Exhibition, 1901, no. 523 (lent by George McCulloch, Esq.)

London, Royal Academy, Exhibition of Modern Works in Painting and Sculpture forming the Collection of the Late George McCulloch, Esq., Winter Exhibition, Fortieth Year, January 4-March 13, 1909, no. 76

London, Royal Academy, Exhibition of Works by the Late Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, R.A., O.M.: Winter Exhibition, Forty-Fourth Year, January 6-March 15, 1913, no. 166 (lent by Mrs. Coutts Michie)

‘for the first-time classical genre subjects were represented with verisimilitude, learning and technical mastery.’ F. G. Stephens, ‘Alma-Tadema’, Artists at Home III

This painting is typical of many of Alma-Tadema’s works from the latter part of his career. From the 1880s onwards his paintings were generally small-scale domestic scenes, illustrating either a minor incident or a moment of repose and contemplation. They are ambitious reconstructions of Rome frequently depicting its wealthy citizens at leisure. Many were painted on an intimate scale, featuring groups of women perched on balconies or exedras overlooking the Bay of Naples.

In Love’s Jewelled Fetter Alma-Tadema conveys a calm Bay of Naples, the area described in ancient sources as a popular resort during the early Empire, where the elite escaped from Rome to their villa maritime. However, the present work and similar compositions of the period were not directly informed by the artist’s travels to Italy but rather by the large Bavarian lake, Steinberger See, where Alma-Tadema’s friend, Georg Ebers, the German Egyptologist, had a villa. Love’s Jewelled Fetter is inspired by the novella, The Amazon (1880, English translation 1884) by Alma-Tadema’s friend, the historian Carel Vosmaer, in which the protagonist is a Dutch artist named Siwart Aisma, based on Alma-Tadema himself. The plot follows the Dutch antiquary’s obsessive study of Roman sculpture collections, as well as his romance with the poet, Marciana van Buren. Alma-Tadema’s scene illustrates a moment where Marciana, shown in violet robes, extends her hand for her companion to examine her ring (the fetter), a token of her and Aisma’s love.

Having witnessed the excavations and seen the skeletons of the ancient cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum emerging, Alma-Tadema was fascinated by the details of Roman everyday life and preferred the realism of Pompeii to the archetype of Athens. F. G. Stephens wrote that in Alma-Tadema’s work, ‘for the first-time classical genre subjects were represented with verisimilitude, learning and technical mastery.’ (F. G. Stephens, ‘Alma-Tadema’, Artists at Home III, 1 May 1884, pp. 29-32). All the artefacts that he depicted in his paintings were authentic copies or actual pieces from ancient times. The bench in the painting is a copy of one from Herculaneum and the statue is Spinario (a Greco-Roman Hellenistic bronze now in the Palazzo dei Conseratori, Musei Capitolini in Rome) which alludes to Aisma’s interests in classical sculpture aligning with Alma-Tadema’s own. Alma-Tadema owned a photograph of the sculpture and it appears in multiple compositions. It is interesting to note that Pieter Claesz (c. 1597-1660), Alma-Tadema’s fellow countryman and a Dutch Golden Age painter of still lives, painted the marble version in Vanitas still life with Spinario (1628, Rijksmuseum), which Alma-Tadema would have known. The objects in the painting all serve the allegorical purpose of reminding the viewer of human mortality and the transience of life. The scene in Love’s Jewelled Fetter seems to occur under the watchful eye of Aisma, who looms from the portrait hanging above them, inscribed Amo Te Ama Me (‘I love you, so love me too’). It is based on a ‘mummy portrait,’ the naturalistic likeness affixed to wealthy Egyptian mummies during the Coptic period, dating from the Roman occupation of Egypt. Ebers was particularly interested in ‘mummy portraits’, and Alma-Tadema’s inclusion further evidences his own voracious curiosity for the Ancient world. It also bears a resemblance to the Portrait of Terentius Neo and his wife which was found in Pompeii and which is housed in the Naples National Archaeological Museum of which Alma-Tadema had a photograph.

During the 1860s in England, a trend towards an eclectic Classicism rose concurrently with that of Aestheticism and as with Aestheticism it yielded a range of disparate expressions. ‘Until Tadema’s arrival’ wrote Burne-Jones, ‘Greek and Roman scenes were shocking things in the hands of the Academy.’ Alma-Tadema brought a new approach to the representation of the classical world, bringing a unique type of historical genre that was a leading force behind the definition of the new classical movement. Fastidiously painted and remarkably illusionistic, Alma-Tadema’s paintings were intended to provide viewers with a compelling sense of daily life in the ancient world. His canvases are like tableaus vivants so realistic are they in their depiction of the human figure within Roman surroundings. The pathos of Alma-Tadema’s depictions of ancient Rome comes from the fact that patently real-life Victorians seem to inhabit his Roman canvases. From our vantage point, we can see that as British power approached its zenith, Alma-Tadema was creating images of an ancient empire that provided the model for Britain’s own modern imperial adventure, in which the Victorians themselves played the starring roles. When Lord Leighton became President of the Academy in 1878, society had become even more receptive to classical subjects and the cult of classicism had evolved. There was a vogue for Greek plays and Leighton, Poynter and Alma-Tadema all designed sets for the theatre. Victorian society was dreaming of a lost world and with Alma-Tadema it was a world that was almost tangible. Alma-Tadema declared: ‘there is not such a great difference between the ancients and the modern as we are apt to suppose … the old Romans were human flesh and blood like ourselves, moved by such passions and emotions.’ (Frederick Dolman, ‘Illustrated Interviews, LXVII: Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema’, Strand Magazine, December 1899, p. 607).

Most artists of the Classical Revival preferred Greek history and mythology to Roman, disliking ‘decadent’ Imperial Roman art and culture because, ‘that craving for display and luxury which pervaded Roman society already in the last century of the Republic and merging in the general appetite for unbridled self-indulgence helped to bring about under the Empire that moral turpitude and shameless putrescence …’ (Frederic Leighton, Addresses, London, 1896, p. 124). Yet it was such subjects that attracted Alma-Tadema and ‘display and luxury’ were the essence of his art and it proved to be immensely popular.

Alma-Tadema trained at a time when ‘history painting’ – images drawing a moral lesson from history or literature – was considered the highest form of art, and knowledge of the visual style of other eras was considered at least as important as painterly technique. By the time Alma-Tadema moved to England in 1870, he was in his mid-thirties and as Wood states, ‘his artistic personality was already formed. His education and training had been entirely continental. His character, his temperament, and his art remained, to the end of his life, essentially Dutch.’ (Olympian Dreamers Victorian Classical Painters, 1860-1914, London, 1983, p. 106). This realistic artistic style was imbued with the tradition and heritage of Dutch interior painting. This tradition was often allegorical, used subtle light effects, and favoured the portrayal of textures and detail in both interior scenes and still life. All of this was achieved with an accompanying quietness of portrayal and an ability to convey emotion while the protagonist is intellectually absorbed. Outwardly the figure can be passive and yet their posture conveys emotion. Following his move to England, Alma-Tadema’s palette became lighter, the atmosphere sunnier and his figures more attractive. He began to paint more outdoor scenes full of sun, sky and marble. He was enthusiastic about Japanese art and this altered his use of perspective making it more abrupt. He had a theatrical eye for striking compositions and framed scenes with strong diagonals and horizontals, often with the eye being led through a door, window or gap in a balustrade to a distant background – recalling the art of Vermeer and Pieter de Hooch. His ability to render surfaces and textiles, command oblique and vertiginous perspectives, to control light, tone and shade and at the same time to have the ability to grasp narrative and drama meant that he was a master of narrative.

Alma-Tadema’s art fell out of favour with the arrival of Modernism. However, his ‘look’ had lasting influence and it defined the epic productions based on antiquity of early and late cinema, such as Quo Vadis (1913), Ben Hur (1926), Cecil B de Mille’s Cleopatra (1934) and more recently Gladiator (2000). Thus, his work has entered the modern psyche and seems familiar to us and his compositions continue to inform our ideas of life in classical times. Alma-Tadema’s work began to be re-appraised in the 1960s and was championed by Allen Funt, the creator of Candid Camera, who bought thirty-five works by him. Funt’s collection was exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1973, in a show called ‘Victorians in Togas’ with an accompanying book. In 1974, Funt sold the entire collection at auction including The Finding of Moses. This painting again came up for auction in 2010 making US$35.9 million – the highest price paid at auction for any Victorian work. High prices continued to be paid for Alma-Tadema’s works and Antony and Cleopatra sold at auction in 2011 for US$29.2 million, nearly six times the pre-sale high estimate of US$5 million.